Warning: this posthas a lot ofis positively dripping with of media. Please pardon the larger-than-usual webpage size as I geek out, reminisce, and stand on a little soapbox in my little corner of the Internet.

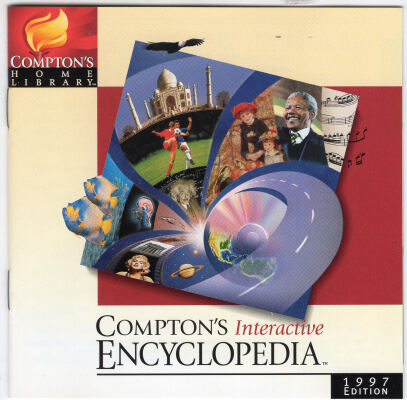

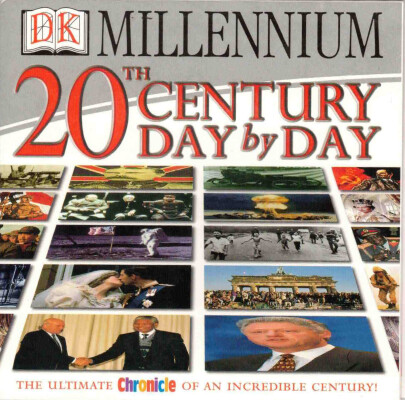

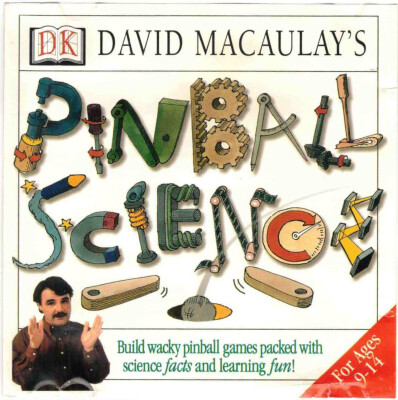

Anyone browsing the stacks of a public library mirror around the turn of the millennium would eventually come across the music-and-software section. Brightly colored photos, generally divorced from their original backgrounds were spliced into abstract arrangement along with bold text and wrapped in a plastic clamshell. Sometimes the CDs were in the original box, other times in a library-specific distribution with a text label that required a child to open each case to see see if the CD label suggested it was something interesting. I was just tall enough at the time to idly flick through the boxes, crack open audio book box sets, and flip through the index card racks that would soon be on their way out.

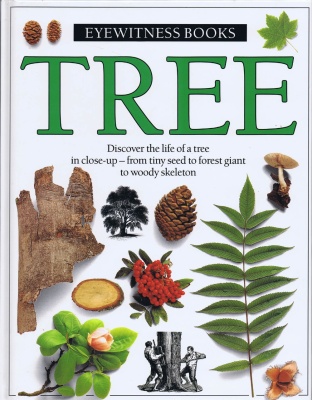

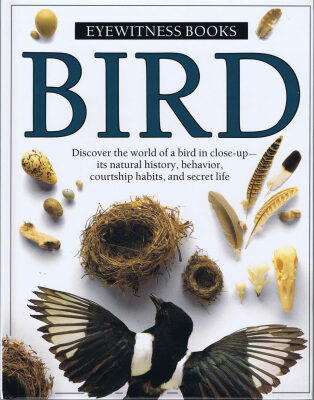

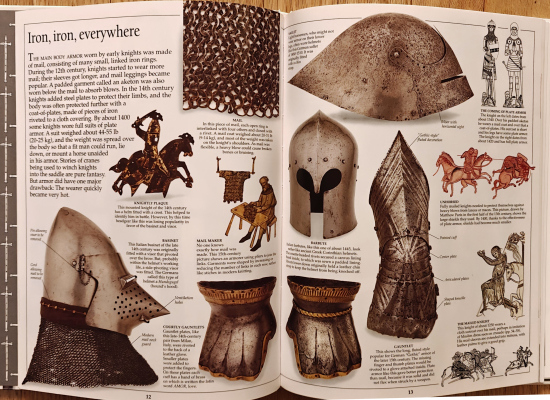

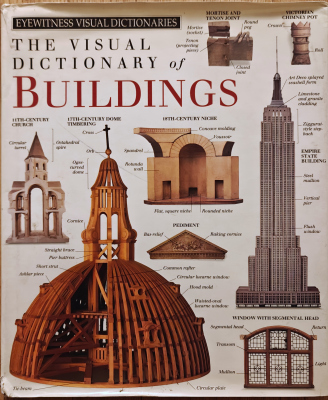

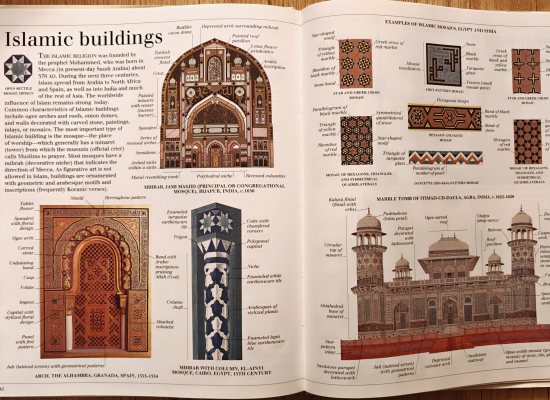

I can still smell the stale air in that library. The sublime 80s portico also served as the backdrop of the first nightmare that I could ever recall during the day. It was a strange and liminal space that I can still meander in my mind. I left thousands of my fingerprints on the topographical globe and corresponding mural of a wall map. I rifled through the DK Eyewitness books as I would later rifle through the Childcraft encyclopedias in my kindergarten class. I would slip books with striking covers and surely obsolete CD-ROMs into my mother's brown library bag (a bag I still have and cherish to this day) on the way to check out.

This is, of course, where I say the library was the catalyst of my book hoarding and general love of the pursuit of knowledge. More than that, the trips to the library burned a very specific sensibility into my mind. While my parents saw the trips as an inexpensive way to pass the time and find whatever software they needed, it was for me a very potent exposure to a fleeting human (or maybe American?) optimism at the dawn of the Internet.

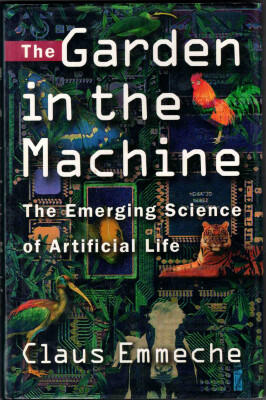

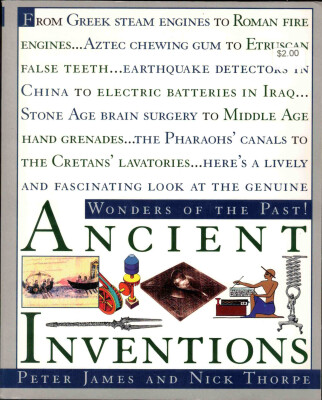

Utopian Scholastic, as described by CARI mirror, is a visual visual style widespread in the late 1990s and early-2000s which features stock image collages in often abstract, education-leaning compositions. A relatively peaceful close of a chaotic century was at hand. There was a vast millennium of human history to reflect on. There was a technology being rapidly deployed that could bring the world closer together. Commercial design, especially in educational materials was imbued with this academic detachment and techno-positivity. Utopian Scholastic writes from place at the end of history mirror, but of course these years were only a vacation from history.

Toys "R" Us' Geoffrey the Giraffe mascot received a photorealistic incarnation around the Peak of Utopian Scholastic design before deciding to live in fantasy again

But before the end of the end of time there was, of course, the beginning of the end of time. And it seems to have begun with the collision of information post-scarcity and the belief in self-guided learning. Computer-aided design and typesetting would invite a generation of kids (and adults!) to explore the world through a new medium.

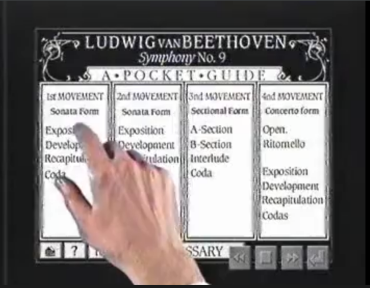

The potential that interactive media could have on education was evident well before the Internet came to prominence. In Douglas Adams' 1990 film Hyperland mirror (Watch Hyperland), the clean, white backgrounds and moving images that would come to define Utopian Scholastic are already present.

Computer-user Adams is perpetually rearranging thumbnails of knowledge, digging deeper and exploring in a manner so clearly prescient to anyone who has ever gone on a Wikipedia bender.

The closing sequence, with its demoscene-style flying CGI, surely influenced the absolute pinnacle of Utopian Scholastic design, the DK Eyewitness documentary series (1995-1998) mirror intro.

Hyperland scene [Extended version with sound]

Eyewitness intro [Extended version in case you couldn't hear the theme music instantly]

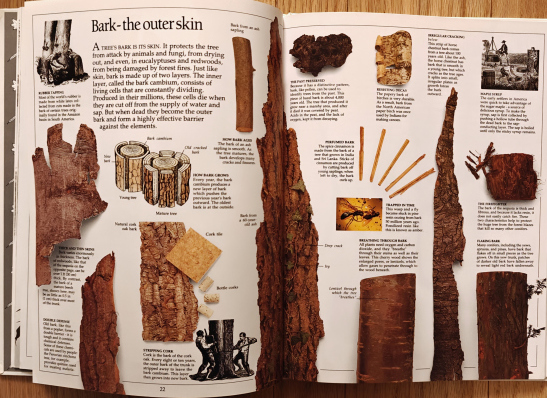

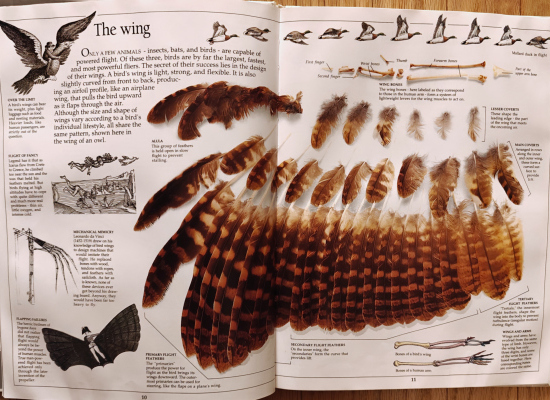

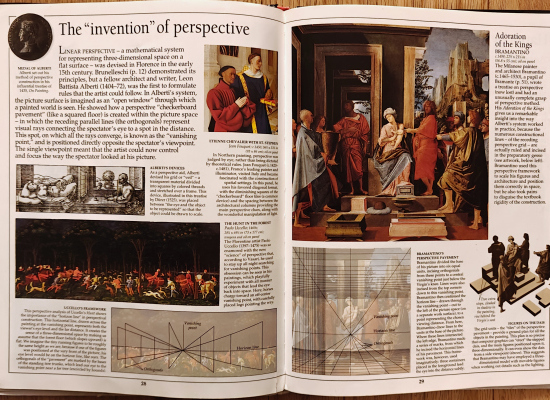

It's an appropriate connection given that DK had been producing the Eyewitness series of eye-popping, but information-dense hardbacks since 1988 mirror). Translating the natural history museum into print, Eyewitness books read more like a cabinet of curiosity than a textbook. In the same manner that the cabinet of curiosity presented a curated assortment of objects from across the domain of natural philosophy (excellent PDR post on this! mirror) to showcase the beauty and wonder of the world, so the Eyewitness series gathers photographs and artwork often divorced of their original context and mixes them together to explore a concept dynamically.

Side note: In case it isn't obvious, I love these books. I have gathered more than 30 of them just by sifting through used book stores (and trying to remember which ones I already have). I've also fallen in love with the gorgeous, but much more dry and taxonomically organized Welcome to the Museum mirror series. I will, however, never forgive Welcome to the Museum producers Big Picture Press for having inconsistent text alignment on their bindings!!

The same stark white background of these books and the non-linear exploration of each topic would become the obvious choice for interactive educational material of the 1990s. In each of these cases, it's the connections between each topic that drives the reader through forking paths of ideas. It's okay to skip whole pages when browsing a topic. The agency and autonomy in the learning process is what I find so compelling in these books. This linking of concepts into an abstract, mental map that becomes personal to each person. It's a kind of dialogue. Like what *Hyperland* predicted for human computer interaction. Artists and software developers of the 90s and 00s delivered on that prediction in such a visually striking way.

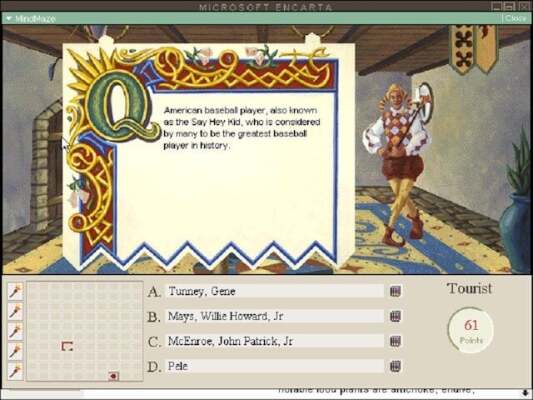

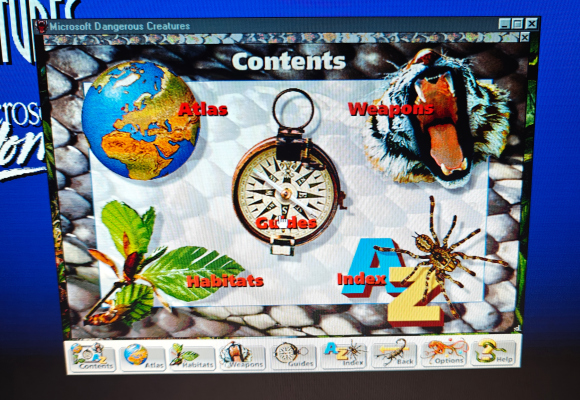

Around the same time as I was laying on the dirty, patterned floor of the Midpointe Middletown library and noisily crunching audiobook cassette tapes back into their form-fitting plastic enclosures, I was regularly going to a babysitter. It was probably 1998/99 and Rocko's Modern Life reruns, serving as a potent and surreal foil for Utopian Scholastic media, were on the TV. One of my strongest memories of my time staying there was watching quietly as the sitter (who was genuinely loving and amazing even if she let us watch cartoons half the day!) conversed with a jester in a 2.5D castle maze. Trivia questions, the answers to which I certainly didn't know if I could even read the words, led further and further in a strange, interactive journey of academic diversion. It would only be this year (2025!) that I would learn that the game was the Encarta Mindmaze mirror, part of the Microsoft Encarta encyclopedia.

Quality content from Microsoft? It used to exist! It's true!

The Mindmaze, more than the fluorescent, side-scrolling tropical fish screensaver or the television, captivated me due to its user-driven meandering. (Hmm I guess Blue Prince scratches that same maze-exploring itch). Like so many other kids of that era, I would go home and spend hours on the family Windows computer and just *look around*. Windows 95, unlike the modern iterations that treat users like an illiterate moron, presented hundreds of settings through a vast tree of interesting dialog boxes. It was no matter that I was too young to comprehend the implications of the settings-- I wasn't foolhardy enough to toy with the fragile family PC of the 90s --the fact that I could see new words in context was an education of its own.

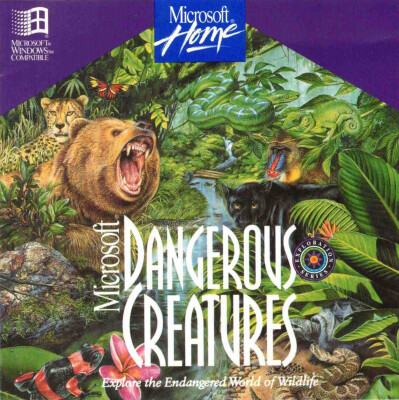

The interactive media corpus built on top of the click-heavy, non-linear framework of the 90s Windows environment (not to mention the Macintosh's prescient HyperCard mirror software) was vast. I had an incredibly difficult time narrowing down the representative pieces of Utopian Scholastic education and home office software to share here. It feels like nearly everything released from 1995 to 2002 echoes the same photo-forward styling with only a spattering of new age stylizing.

While Dorling Kindersley was obviously at the vanguard, I've come across many other examples of books and print media from my collection that easily fall into the Utopian Scholastic umbrella.

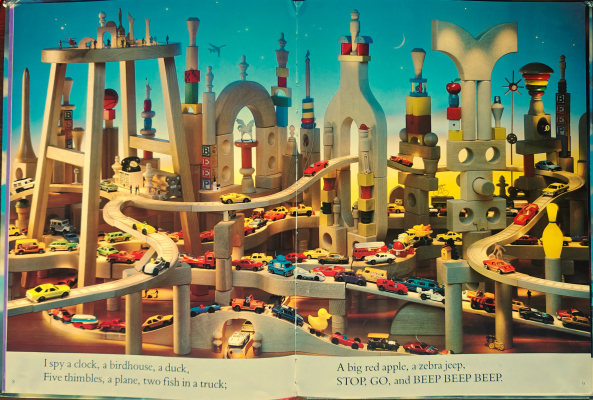

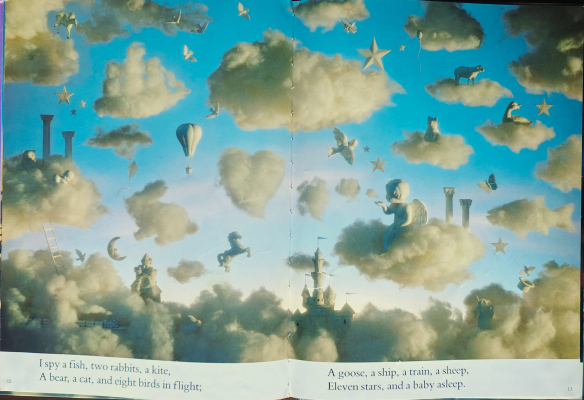

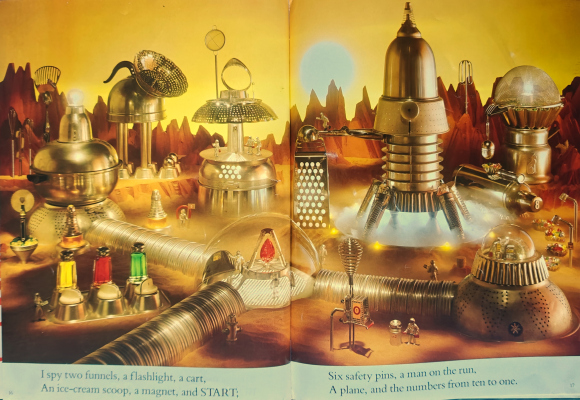

I'd personally like to go out on a limb and say the I Spy Fantasy book speaks to me in a very Utopian (though maybe not wholly scholastic) manner. And, yeah, maybe I just wanted to remind people how cool the toy block city is. Mark my words I will make an OpenTTD mirror texture pack based on this some day!

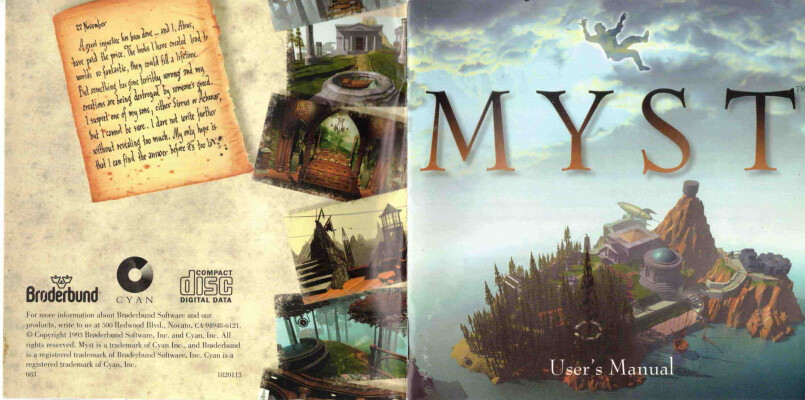

Ha ha! I got this far without talking about Myst mirror. I cannot think of a piece of period software that better reflects on the solitary journey of investigation. While the game has a potent eeriness, the user is (nearly) detached from the events: an observer and wanderer foremost. I'm ashamed to say that despite having the entire series I've only played an hour or so of Myst in scattered bursts throughout my life. I'm almost afraid to finish it in case the plot does not live up to the magical atmosphere in the first few scenes.

Myst, of course, launched a whole category of media-- immersive puzzle solving games. A genre of entering a memory palace mirror dreamed up by the games author. It's perhaps that potency of travelling through three-dimensional space (even if by digital illusion) that places the story (and the knowledge associated with it) so firmly in the players mind.

As exemplified by Myst, the exploration of the Utopian Scholastic era was a solitary endeavor. While many dining chairs could inevitably crowd around a computer desk, the experience was fundamentally between the computer user and the publisher of the software. While threshold for creating software could be quite low and BBS's abounded with quirky, outrageous, or totally explicit content, the software that had the greatest distribution was sanitized and generally appropriate to run on a library computer. Just like a physical encyclopedia, the CD-ROM manifestation takes time to compile and disseminate. It could be quickly out of date. It couldn't easily ingest valid user contributions. It could have the biases of the editor. But it also couldn't be deleted overnight by the incoming political regime.

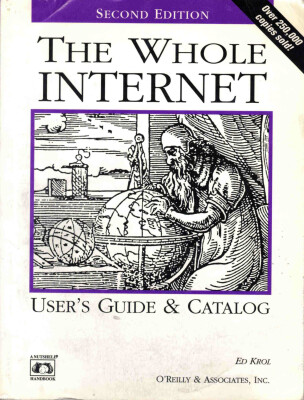

This was an age before the Internet had wide adoption by the general public. Only with the spread of broadband n the early 2000's would the Internet gain the same character of vivid imagery and complex narratives as boxed software. By then, the world had changed and development of blogging and social media (see the phenomenal Cybercultural series on the evolution of the Internet in the dotcom era mirror) fundamentally shifted what information was available to someone logging onto their computer. The democratization of publishing and instantaneous content transmission removed the editorial filter on computer media up to that point. But the Internet, the culmination of the Utopian Scholastic ideal of a perfectly connected world open to anyone who wanted to explore, would prove to be its downfall.

!!! Stop here if you were just here for the pictures. Beyond this point is a long rant followed by a measured dose of hopium. !!!

One can think of Utopian Scholastic as the artistic representation of information post-scarcity. It's the Internet of the Library that could pull from any book from anywhere in the world. But of course the corpus of public-library-appropriate books is an incomplete view of humanity. And it surely isn't going to make any money.

The transition out of Utopian Scholastic design into the age of Frutiger Aero mirror (CARI mirror) was fairly gentle. Flash website design often maintained a playful element even if photo realism would fall by the wayside. Microsoft was altruistic enough to include Space Cadet Pinball without ads or a subscription in Windows XP. Apple's interfaces on the iPod Touch and OSX Leopard were bright and covered in gradients. It was still an age of experimentation. But for many users, the Internet was shrinking to just a few websites: a search engine with increasingly less click-through and social media. With the advent of smartphones the Internet would begin to be filtered through the constraints of an app.

I'm trying my damnedest here to be concise so I'll utilize a metaphor. In the mid 2010s, during my internship at Intuit. I witnessed firsthand how the UI designers for TurboTax were honing user interface design as a weapon. In the study, they would watch a user's mouse move around a demo layout. The goal was to maximize the number of purchases of an upgrade regardless of the user's situation. The UI was designed to be intentionally misleading. By utilizing human fear and hesitation, they would swindle people into clicking for TurboTax Deluxe. They didn't need Deluxe! They didn't even need to pay anything! Filing your fucking taxes online is free for half the US! This is the way that the dream of an Internet for the people was crushed.

As far as I'm concerned, this broached an era best represented by Corporate Memphis mirror. The disingenuous minimalist design is a reflection the minimization of user agency. The design centers around presenting the flat user stories as how the user should feel and act. The invitation to explore and grow is gone. With each tweak to a social media algorithm or mandatory software update the user is cast into the role of a passive consumer, a data point on an engagement graph. The Internet was not unique in this bait-and-switch of profit maximization. One can look to cable television and Clear Channel radio to see what slop people are expected to consume.

Note: This is where I'd put a picutre of Corporate Memphis but I refuse because I can't fucking stand it

In Douglas Adam's *Hyperland*, the user is in control, the software agent is subject to their whims. In modern UI, search engine, and large language model (LLM) interface design, the user is led. At the very least, the user is given a constrained view of the world that fits into some company's monetization regime. Even for inquiring minds, the instant answers provided by knowledge engines aren't meaningfully retained. A 2025 MIT study mirror compared topic retention between essay-writers who used an LLM, a search, engine or neither. It suggests the learning was "not internally integrated, likely due to outsourced cognitive processing to the LLM." The same study found a decided echo-chamber effect in which the unique perspectives of individuals were suppressed in favor of the canned "correct" answer. Much grumbling has been made about the post-truth age. But it often feels like the world has moved into a post-learning age.

I'm drawn to Utopian Scholastic because it represents a sort of digital incarnation of the archetypal lone antiquarian pouring over countless tomes in a high tower; sequestered from the superficial world below. The knowledge within a childrens' encyclopedia may not be so arcane as that of the alchemist, but the revelations of the wonders of the world are still personal. And like the path of the alchemist, the focus in this isolated, pre-social-media world, is primarily inward.

Find me a medieval monk who could dream up such hells and ecstasies as could be found on the early web

I resonate with this caricature even as I know the path of the alchemist terminates in the impossible. Growing up as an only child with more existential curiosity than my peers, I learned to love my solitude among the woods, my family's books, and a hand-me-down PC. Because of this, or, perhaps because of some uncurable habit of chronic introspection, I've always felt somewhat aloof from modern society. Indeed, it never was as perfect as described in turn-of-the-millennium PC encyclopedias. History kept marching on and it really wasn't pretty.

I have had a generally fantastic life. I'm even pretty decent at socializing when I stop being condescending. But the growing awareness of human caused destruction has definitely clouded my outlook. I've considered myself a misanthropist for much of my life. Sometimes it takes a singular book or a video game to get me to pick one side or the other.

SPOILERS! Maybe don't read this section if you haven't played both the Talos Principle and the Talos Principle 2. I promise this is the last quote block in this post.

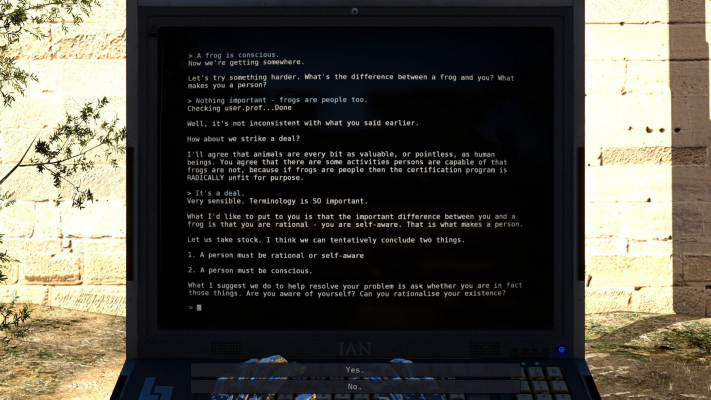

The Talos Principle mirror is a visually stunning puzzle series taking place after a human extinction event. The protagonist explores the concept free will through solitary interactions with puzzles and classical literature. The player may ultimately choose their ending to the game, but the main ending is one in which the player seeks independence of thought. It's Portal mirror) dressed in a toga, the Utopian Scholastic ideal of technology, solitary exploration, and thought-provoking erudition.

The sequel mirror is framed differently. The player is immediately put into a society of diverse (and sometimes insufferable!) characters. I found myself disappointed that I sometimes had to follow along the plot line with people that were actively challenging my beliefs. (I really wanted to chuck Byron off a cliff, okay) But the game provided me with beautiful meanderings through a pristine biomes spinkled with beautiful brutalist megaliths. And the forking path of choices in the game does allow for a more pessimistic view toward humanity even if the gradient was pretty abrupt. I ended up with an ending. It wasn't the "best" one, but it left me with the thought: without humans, who is there to appreciate the splendor of the universe? How can we throw away our DNA: the triumph (or at least the brave experiment) of gaia's serendipitous evolution? Who else could we entrust to seeding life throughout the universe to protect against the destructive whims of an unfeeling, undiscriminating universe?"

Utopian Scholastic and its sabbatical from history is places humans as observers within the universe rather than active members in it. It lacks the call to action that is demanded by science and art. Of course, Utopian Scholastic content is toned down for kids-- it's challenging to put a memento mori on an elementary school computer. And even meek suggestions for action can be construed as some kind of biased, political motive. On a more practical level, the existential problems facing humanity are hard! Graphic design's goal isn't really to predict the future or explain the meaning of life. Yet, it's a branch of the potent world of art. And the invulnerable, stoic optimism exuded by Utopian Scholastic contrasts harshly with the crooked march of human progress. Knowledge without context of life's fragility is bound to lead to inaction.

Some of my pessimism, so antithetical in the bright-eyed days of the late 90s, is derived from the disconnect between the utopia presented in virtual encyclopedias and the self-sabotaging society I would come to enter. Our ability to comprehend the scope of our actions is (probably) unique in all eons in the history of life. Yet we refuse to believe anything that would challenge the mandate of unbounded capital growth. This superficial introversion fails to incorporate mankind's place in the comsos into it's reason for existing1. Much like an alchemist seeking the philosopher's stone without first righting themselves within the supernatural world, materialistic human progress ignores our precious capacity for higher thought.But it's nihilistic, meaningless to surrender to the future prescribed by corporate defeatism. We don't have to accept our doom brought on by ourselves or the machinations of the universe. Humans are, to our current understanding, unique in the world by the power of our cognition. While we are often agents of hate and destruction, we can be authors of creation, engineers of mending, restoration, and preservation. We have the power of hope and resilience. It's fruitless to squirrel ourselves away and refuse to face the place we occupy in existence. We must be invested in the world that we live in. The insights we discover in the erudition of our daily lives must not be discounted. Our gift of cognition must be respected in order for it to develop. And if we want to respect our cognition, it must be put into practice.

I'm grateful to have found this amended idealism in the dusty outskirt of the web that I reside. It's not the blind techno-optimism of an Internet that is obsessed with sales figures. It's more in line with DIY sensibilities and solar punk mirror. Rejecting the corporate model of a captive Internet, individuals can be empowered to find the communities that foster the joy of being human. They can be encouraged to grow and create. They can take pride in work that came about through their own effort. Wikipedia is a glorious bastion of human-centric knowledge aggregation mirror in an era when Encarta's Microsoft is shilling a genie in the form of AI. Anna's Archive provides a means of preserving the corpus of human knowledge without relying on an entity that is subject to a bottom line or the whims of their leaders. Personal blogs and community forums continue to document unique, individual experiences and provide guidance to others without seeking compensation or fame. The dream of an Internet incorporating all of humanity's cognition for the good of all people is not dead. It's just sick. The tools to power a healthier online space are available, but they aren't owned by shareholders.

The Utopian Scholastic approach of human-centric education lives on today. Interactive learning is more powerful than ever mirror. Games like Civilization, Crusader Kings, Kerbel Space Program, and everything Zachtronics put out, offer opportunities for essentially academic learning alongside engaging gameplay. But even games that aren't explicitly full of historical lore or science provide their own mental stimulation through open-endedness: Minecraft (though open source Luanti mirror is certainly less on-rails these days) and tycoon games. Others reveal mathematical beauty like the gambling-adjacent Balatro. Still others are thought-provoking or meaningful in the manner of a novel: The Stanley Parable, Chants of Senaar, or Gone Home. It'd be tiresome to list all of the works of computer media I can think of which strike up a dialogue with the player, encourage creativity. and inspire joie de vivre that can translate into the physical world. Time spent at the computer can be meaningful. The user just needs agency in that interaction.

Beyond the stripped-down approach I've taken to my online life, I've done my best to foster a sense of curiosity in my kid. I've gotten him his own topographical globe reminiscent of the one I spent so much time with at the Middletown library so many years ago. Our bookshelves bear a 1980s-vintage Childcraft encyclopedia collection and as many Eyewitness books as reason allows. I don't know if these will have the same effect on him as they had on me. And while I often can't help pulling one from the shelf and reading with him, I want him to develop the fascination naturally. I do believe independent thought is still possible in the third decade of this millenium.

At the time of this writing, we're closing out 2025. A quarter of a century has passed from the peak of Utopian Scholastic design and the not-quite end of history. I find renewed-but-augmented hope for technology as a beneficial, uniting force. I believe that the challenges we face on the planet can be overcome if we are first willing to accept that we are capable. We don't require the intercession of some messianic AGI that would ultimately maintain existing social inequality anyway. Human dignity demands that we acknowledge our ability, even by means of play, to approach intricate problems and overcome incredible challenges. People are at their best when they are given the chance to explore, experiment, be wrong, and learn. Only then can we prove our resilience as a species and preserve this noble accident of a biosphere.

Thank you for hanging on through this blog post. Best wishes to you in whatever era you've come across this.